The US has always insisted that the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were necessary to end World War Two. But it is a narrative that has little emphasis on the terrible human cost.

I met a remarkable young man in Hiroshima the other day. His name is Jamal Maddox and he is a student at Princeton University in America. Jamal had just toured the peace museum and met with an elderly hibakusha, a survivor of the bombing.

Standing near the famous A-Bomb Dome, I asked Jamal whether his visit to Hiroshima had changed the way he views America's use of the atom bomb on the city 70 years ago. He considered the question for a long time.

"It's a difficult question," he finally said. "I think we as a society need to revisit this point in history and ask ourselves how America came to a point where it was okay to destroy entire cities, to firebomb entire cities.

"I think that's what's really necessary if we are going to really make sense of what happened on that day."

It isn't the sort of thing you often hear said by Americans about Hiroshima. The first President George Bush famously said that issuing an apology for Hiroshima would be "rank revisionism" and he would never do it.

The conventional wisdom in the United States is that the dropping of atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended the war, and because of that it was justified - end of story.

Is that really the end of the story?

It's certainly a convenient one. But it is one that was constructed after the war, by America's leaders, to justify what they had done. And what they had done was, by any measure, horrendous.

It didn't start on 6 August. It had started months before with the fire bombing of Tokyo.

On 9 March 1945, 25 sq km (9.7 sq miles) of Tokyo were destroyed in a huge firestorm. The death toll was as large, or even larger, than the first day at Hiroshima. From April to July the relentless bombing continued in other parts of Japan.

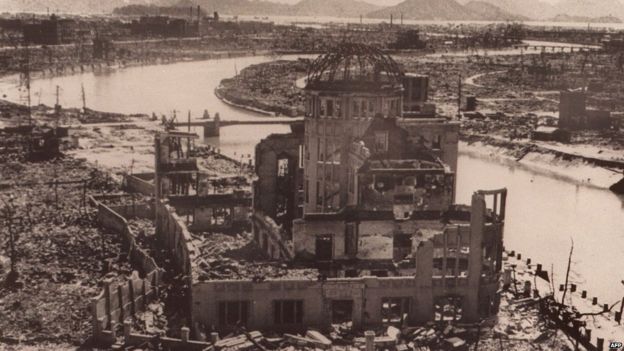

Then came Hiroshima.

'There was no sound at all'

Keiko Ogura had just celebrated her eighth birthday. Her home was on the northern edge of Hiroshima behind a low hill. At 08:10 on 6 August, she was out on the street in front of the house.

"I was surrounded by a tremendous flash and blast at the same time," she says.

"I couldn't breathe. I was knocked to the ground and became unconscious. When I awoke I thought it was already night because I could not see anything, there was no sound at all."

What Keiko witnessed in the following hours is hard to comprehend.

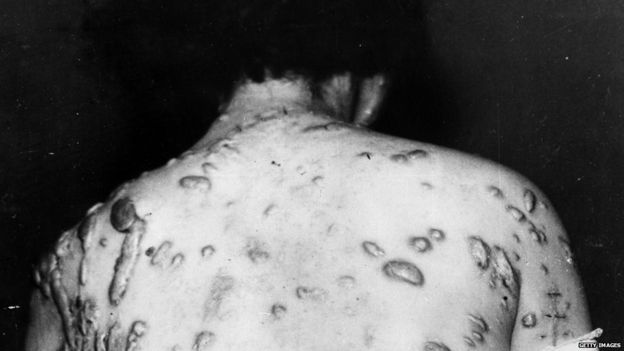

By mid-morning, survivors of the blast began pouring out of the city looking for help. Many were in a terrible state.

"Most of the people who were fleeing tried to go to the hillside. There was a Shinto shrine near our house so many came here," she says.

"Their skin was peeling off and hanging. At first I saw some and I thought they were holding a rag or something, but really it was skin peeling off. I noticed their burned hair. There was a very bad smell."

A deliberate civilian target

Eighteen-year-old Shizuko Abe was staggering out of the city, the whole right side of her body burned, her skin hanging off. Now 88, she still bears the terrible imprint of the bomb on her face and hands.

"I was burned badly on my right side and my left hand was also burned from the bomb. Fire was coming closer… We were told to run to rivers when hit by air raids so people jumped into the rivers.

"So many bodies were floating in the river that I could not even see the water," she says.

Somehow, despite the agony, she staggered to a medical station.

"They did not even have any dressing for the wounds. Many injured people lay their bodies down under the roof, so I found a place there as well to lie down. People around me were calling out 'Mother it hurts, Father it hurts'.

"When I stopped hearing that, I realised they had died right next to me."

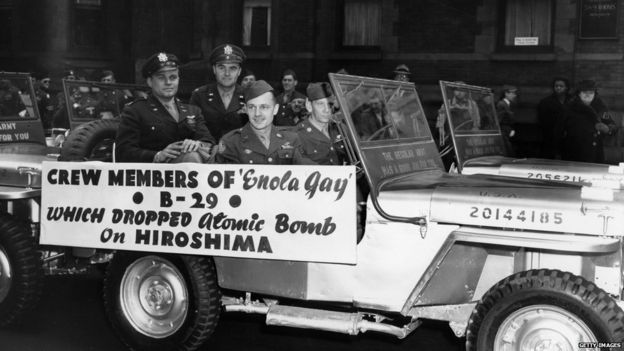

Hiroshima was not a military target. The crew of the Enola Gay did not aim at the docks, or large industrial facilities.

Their target was the geographical centre of the city. The bomb was set to explode 500m (0.3 miles) above the ground for maximum destructive effect.

On the ground many survived the initial blast, but were trapped in the wreckage of their homes under wooden beams and heavy tiled roofs. Then the fires began.

Ms Abe remembers hearing the cries for help from beneath the debris as the flames swept forward.

"They were such sad voices calling out for help. Even 70 years later, I can still hear them calling out for help," she says.

No-one is sure how many died on that first day. Estimates start at 70,000. More than eight out of 10 were civilians.

If you look up "Hiroshima in colour" online, you will find some remarkable film that is now kept in the US national archives.

A US military team and Japanese camera crew shot more than 20 hours of film in March 1946. It is the most complete and detailed visual record of the after effects of the first atomic attack.

There is high-quality colour footage of the horrific scarring caused by flash burns from the bomb. There are injuries that had never been seen before.

'They should not thank the bomb'

What is all the more remarkable is that the film was not seen in public until the early 1980s. It was marked secret and suppressed by the US government for more than 30 years.

Instead, Americans were told a sanitised narrative of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: that a great scientific endeavour had brought quick victory, and saved hundreds of thousands of lives on both sides.

Decades later when Ms Ogura travelled to the Washington DC to see the unveiling of the Enola Gay at the Smithsonian Museum, she was astonished to find this version of history still holding sway.

"Many American people said to me, '"Congratulations, you could come here thanks to the bombing! Without the bombing you would have to do hara-kiri, you know, commit suicide'."

"That is a very awful excuse. We do not blame the Americans, but they should not say that thanks to the bomb so many people could survive."

A lifetime of radiation secrecy

The atomic bombing has left one final legacy that sets it apart from all the other horrors of World War II.

In the weeks after the bombing otherwise healthy people began dying of a strange new illness. First they lost their appetite, then they began to run a high fever.

Finally strange red blotches began appearing under their skin. No-one knew it at the time, but these people were dying from radiation poisoning.

To this day many hibakusha keep their pasts a secret, afraid that their families will be discriminated against because of the fear of radiation.

"I had bad burns and looked deformed so I could not keep it secret," says Ms Abe. "My children were discriminated against. They were called 'A-bomb children'."

Tears fill her eyes as she describes what happened to them.

"They told me they had to choose a different route to come home from school because they were bullied and chased by the other children. I felt the pain my children had to go through because of their mother, because of me."

Even today some hide the fact that a grandparent is an A-bomb survivor, afraid their children may find it difficult to find a husband or wife.

The human cost

It is said that those who don't know their own history are condemned to repeat it. Japanese leaders are rightly criticised for their continued attempts to whitewash Japan's WWII crimes in China, Korea and South East Asia.

It is also true that terror bombing was not invented by the United States. The Nazis unleashed it at Guernica in 1937 and again on British cities in 1940.

The Japanese bombed Chongqing for six years. The British destroyed Dresden and many other German cities.

But no other bombing campaign in WW2 was as intense in the destruction of civilian lives as the US bombing of Japan in 1945. Between 300,000 and 900,000 people died.

As Jamal Maddox put it to me so well, how was it that the country that entered the war to save civilisation ended it by slaughtering hundreds of thousands of civilians?

By Rupert Wingfield-Hayes

sourche: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-33754931

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου