Illustration: Simon Pemberton

It has been a bad few months for western democracy. Over the summer we discovered that while democratic citizens and their elected politicians were going about their everyday business, the secret services were routinely eavesdropping on everything they did. It was bad enough to suppose that the politicians were conniving in this. More disturbing was the thought that even the politicians were being kept in the dark about what was going on.

Then, in September, we had the spectacle of western leaders trying to take a lead on Syria, only to be stymied by their legislatures, which wouldn't let them do anything (the British parliament didn't express a decisive view, not even against the use of force; it simply rejected all the options put to it, like a sulky child). Principled positions on both sides of the argument got lost in the fog of partisan politicking. As Obama, Cameron and Hollande floundered around looking for a workable policy on Assad's chemical arsenal, Putin stepped in at the last moment to save the day. It was a humiliation he compounded with a crowing article in the New York Times that highlighted the advantages of mature statesmanship over democratic skittishness.

Then things got worse. For 17 days in October the US government ceased to function altogether, while bitter infighting in Washington took the country to the brink of a disastrous default. The sight of American politicians playing their absurd game of chicken with the global economy left the rest of the world with conflicted emotions, ranging from despair to barely concealed glee. Putin smirked. The Chinese tut-tutted. Bureaucrats in Brussels gave a world-weary sigh. Politicians who do not have to worry about getting re-elected or who face only docile and compliant parliaments found themselves looking on with a mixture of pity and contempt. Imagine trying to do serious politics under the relentless pressure of eternal democratic squabbling, with barely enough time to breathe, let alone to think straight. Is it any way to run a government?

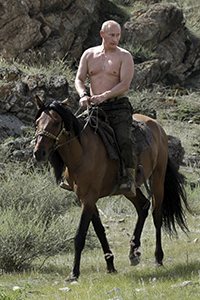

Putin on holiday. Photograph: Alexsey Druginyn/AFP/Getty Images

Putin on holiday. Photograph: Alexsey Druginyn/AFP/Getty Images

Those of us who live in the western democracies might sometimes be tempted to agree. Dictator envy is a habitual feature of democratic politics. We don't actually want to live under a dictatorship – we still have a horror of what that would entail – but we do envy dictators their ability to act decisively in a crisis. For all his many faults, it is hard to imagine that Putin is often in the dark about what his spooks are up to. We may laugh at allthose photographs of him stripped to the waist and hunting wildlife. Still, this is evidently a politician who knows how to go for the kill. Do ours even know what they are hunting for? While Obama was trapped in Washington grinding out a provisional solution to the shutdown, China's leaders were exploiting his absence from the world stage to promote the pragmatic benefits of their political system.

Chinese politicians have the advantage of being able to take the long view, freed from the remorseless demands of the electoral cycle. At the same time, China's technocrats can cut through all the checks and balances of democratic politics to take speedy decisions. They don't have to worry about squaring parliament or public opinion before they act. I have lost count of the number of times I have been told by western academics how refreshing it is to deal with Chinese politicians who can get things done. If you have an exciting plan to green an urban environment, or recalibrate a transport system, or reboot an entire industry, take it to China, where they might actually give it a go before it becomes stale. None (or at least vanishingly few) of these western academics actually want to adopt Chinese state capitalism, which they consider an oppressive and illiberal system. They are invariably still wedded to democracy. They just wish it could be similarly decisive.

The irony of dictator envy is that it goes against the historical evidence. Over the last 100 years, democracies have shown that they are better than dictatorships at dealing with the most serious crises that any political system has to face. Democracies win wars. They survive economic disasters. They adapt to meet environmental challenges. Precisely because they are able to act decisively without having to square public opinion first, dictators are the ones who end up making the catastrophic mistakes. When dictators get things wrong, they can take the whole state over the cliff with them. When democratic leaders get things wrong, we kick them out before they can do terminal damage.

Yet that is little consolation in the middle of a crisis. The reason we keep succumbing to dictator envy is that it requires steady nerves to take the long view when things are going wrong. The qualities that give democracies the advantage in the long run – their restlessness and impatience with failure – are the same qualities that make it hard for them to take the long view. They look with envy on political systems that can seize the moment. Democracies are very bad at seizing the moment. Their survival technique is muddling through. The curse of democracy is that we are condemned to want the thing we can't have.

The person who first noticed this deeply conflicted character of democratic life was a French aristocrat. When he travelled to the US to study its prisons in 1831, Alexis de Tocqueville shared the common 19th-century prejudice against democracy. He thought it was a chaotic and stupid system of government. By the time he finished his journey a year later, he had changed his mind. He decided that American democracy was a lot better than it looks. On the surface, everything appeared a mess: bickering politicians, vituperative and ill-informed newspapers ("The job of the journalist in America", Tocqueville wrote, "is to attack coarsely, without preparation and without art, to set aside principles in order to grab men"), distracted citizens. No one was able to exert a grip. There was far too much noise, not enough signal. But over time this surfeit of noise produced an adaptable politics that never sat still for long enough to get stuck. The raucousness of American politics was a sign of its essential health. Americans kept stumbling into holes and then back out of them. More mistakes are made in a democracy, Tocqueville wrote, but more mistakes are corrected as well. More fires get started by Americans. More fires get put out by them too.

Tocqueville's genius was to spot the likely psychological effects of living with such a system. It could go one of two ways. Many people would be made highly irritable by the constant inability of democratic politics to get its act together. Tocqueville called democracy an "untimely" form of government because it never seemed to rise to the occasion. When things look really bad, democratic politicians are often to be found bickering over inessentials. Yet when the crisis has passed, these same politicians turn out to have found a way to pull through. It is all very undignified. As a result, Tocqueville suspected that democratic citizens would always have a soft spot for kings and tyrants, who at least knew how to put on a show. Democracies dream of rescue by the politician who can bang a few heads together. When that politician fails to show up, their frustrations will bubble over. Anger and disgust are never far from the surface of democratic life.

Last month's protest by US federal government workers calling for an end to the shutdown. Photograph: Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call

Last month's protest by US federal government workers calling for an end to the shutdown. Photograph: Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call

However, the other likely psychological consequence of democratic untimeliness is complacency. If it is true that democracy is not as bad as it seems, then it is tempting to imagine that no crisis is ever as serious as it looks. Things will be all right in the end, so long as we don't overreact. Tocqueville spotted that American democracy was founded on faith: people had to believe such a messy system would see them right in the end. The danger was that their faith in democracy would blind them to the stupid mistakes their politicians were making. Some crises, even for Americans, really are as bad as they seem.

Tocqueville's analysis is the best guide to the workings of modern democracy throughout its history, right up to the last few weeks. The democratic mindset is to be despairing and blithely confident all at the same time. Just look at the behaviour of America's current crop of political desperadoes. Surely you would only shut down the government if you thought that the system was working so badly that it is almost beyond repair. Desperate times require desperate measures. On the other hand, it is also true that you would only shut down the government if you thought the system worked well enough to survive whatever you could throw at it. Nothing is ever as bad as it seems. Scorched-earth Republicans have effectively given up on American democracy at the same time as having unlimited faith in it. They don't want to ditch it, certainly not for Chinese state capitalism (anything but that). But nor can they bear to put up any longer with its messy compromises. Furious impatience and shoulder-shrugging fatalism are the twin vices of democratic life. The same politicians display them simultaneously.

It has always been like this. The history of democracy throughout the 20th century is a story of repeated crises during which politicians and publics have been torn between the twin impulses to overreact and to underreact to the dangers, without ever finding the balance between them. Dictator envy is never far from the surface. When the defining crisis of the century erupted in 1914, it became a permanent feature. Once it was clear that the first world war would not be over by Christmas, anxiety started to bubble up about whether the democracies had what it took to defeat the German military machine. Would they ever get their act together? In October 1915, the Times hosted an anxious debate on its letters pages about the relative merits of democracy and autocracy under conditions of total war. The consensus view was that democracy prioritised the wrong things. As one letter writer put it, the German emperor could promote politicians on the basis of their achievements, whereas "a democracy has no such knowledge: it chooses its leaders because they are well born, because they are skilful speakers, because they are good fellows." In October 1915, the focus of the war was in the east, where the Germans were achieving military success against the Russians, whereas the British had just suffered humiliation in the Dardanelles at the hands of the Turks. It was clear who the letter writer had in mind. The politician responsible for Britain's failure was Winston Churchill. The German general setting the pace was Erich Ludendorff. The trouble with democracy was that it gave power to lightweights such as Churchill. The strength of autocracy was that it promoted heavyweights such as Ludendorff.

The cult of Ludendorff, who in 1916 became with Hindenburg the effective dictator of Germany, grew in the western democracies throughout the war. People in Britain, France and the US didn't want to be ruled by Ludendorff. They just wished their own elected politicians could be more like him. In 1917, with America having joined the fight, the Atlantic Monthly sent its young star journalist HL Mencken to Germany to profile the great man. Mencken was convinced that Ludendorff represented the reason Germany would come out on top: he was ruthless, pragmatic and decisive. The contrast with America's president Woodrow Wilson couldn't have been more stark. Wilson was all words and no action; a ditherer who had promised to keep America out of the war, before changing his mind and taking the country in. Ludendorff, who rarely spoke in public, was the silent destroyer. Democracy appeared much too confused and chaotic to compete.

Mencken was wrong. Ludendorff suffered from the failing of all dictators: he wasn't adaptable enough. When his great plan to win the war in 1918 failed to deliver the decisive breakthrough, he had no fallback. He just ploughed on to the bitter end, until he and his army fell apart. Wilson the ditherer turned out to the adaptable one. The western democracies won the war because, although they made more mistakes, they corrected more mistakes as well. They changed policy, strategy, generals and politicians; chopping and changing until they found something that worked. France got through three prime ministers in a matter of months during the dark days of 1917, before stumbling on Clemenceau, the man who would save the country. At the time, French politics looked like the worst of democracy: fractious, petty-minded and prone to panic. Only in retrospect is it clear that this restless dissatisfaction is what made the difference. Western democracy survived the first world war because it was chaotic enough not to get bogged down by its own failings.

Victory wasn't enough to put an end to dictator envy, however. Wilson, having defeated the autocrats, wanted to match them for decisiveness. Now he was competing with Lenin: to see off the Bolshevik menace, he hoped to create a world safe for democracy. But democracy wouldn't let him. The restless impatience that got the democracies through the war scuppered Wilson's attempts to build a lasting peace. He wanted people to take the long view. The voters were fixated on more immediate concerns: wages, jobs, prices, revenge. The US Senate blocked America's entry into the League of Nations. The British and French electorates reverted to the national interest and their politicians to petty infighting. Democracies achieve victory in epic struggles such as the first world war because they keep moving on from their mistakes. But they keep moving on from their victories too, which is why they squander them.

Roosevelt, 1904. Photograph: AP

Roosevelt, 1904. Photograph: AP

This pattern has repeated itself throughout the following century. In the early 1930s, at the height of the great depression, dictator envy was rife. It was widely assumed that western democracy would only survive if it took a leaf out of the dictators' book. Stalin, Mussolini and Hitler looked like the men of action who could take the tough decisions needed to stave off disaster (Mussolini was particularly admired in this period for his hackneyed ability to get the trains to run on time). Elected politicians looked like miserable pygmies by comparison; too frightened of their electorates to take charge and too hamstrung by their parliaments to change course. But Franklin Roosevelt showed that this analysis was wrong. He was a notoriously changeable politician, never quite sure what he was doing or what he believed in but willing to try most things on the off chance they might work. Throughout his long presidency there were regular predictions of impending disaster: either the country would be ruined or Roosevelt would turn out to be a dictator after all. Neither came to pass: under Roosevelt's chaotic but resourceful leadership the country muddled through. It was the dictatorships that fell apart in the end. Barack Obama is no FDR, but the criticism he faces takes the same form. Some accuse him of being a dictator; others of being an inveterate ditherer. The truth is that he is neither. He is just a democratic politician doing his best to improvise a way out.

During the cold war there was barely a moment when commentators in the west didn't worry that the fight was being lost because the Russians were so much more ruthless than we were. Elected politicians were too busy fretting about getting re-elected to devise a coherent strategy for ultimate victory. They kept missing their chance. This fear persisted through the 1980s, even as the cold war was finally being won. In the Reagan White House, full of gung-ho cold warriors, the book everyone read (according to speechwriter Peggy Noonan) was How Democracies Perish, by a gloomy, pretentious French intellectual called Jean-François Revel. Like everyone else, Revel had spotted that the Soviet system was in deep trouble: communism didn't work. Still he argued that it would drag western democracy down into the grave with it because the democracies were too indecisive for the brutal politics of the endgame. When the Soviet Union fell apart, the west would not know how to take advantage. The endless distractions of democratic politics would get in the way. So the hard-headed tyrants in the Kremlin, with nothing to lose, would run rings round us. Once it came to the crunch, democracy would fail to rise to the occasion.

The fall of the Berlin war. Photograph: Tom Stoddart Archive/Hulton Archive

The fall of the Berlin war. Photograph: Tom Stoddart Archive/Hulton Archive

But when it came to the crunch, democracy didn't need to rise to the occasion. The end of the cold war was a lot like the end of the first world war: victory took the victors by surprise. Democracy won not just in spite of its distractions but because of them. While the Soviets were digging themselves a hole that they couldn't get out of in Afghanistan, western citizens watched television and went shopping. Then one night they turned on their TVs and discovered that the Berlin Wall had come down. As in 1918, the temptation existed to turn this triumph into a vast morality tale. It must mean something momentous that democracy had won such a crushing victory. More, it must be an opportunity for democracy to cement its grip on the world as the rightful system of government for everyone. But it didn't mean anything momentous. After the wall came down, western citizens just carried on shopping.

Victory in the cold war was squandered as surely as victory in the first world war had been. In part this was a consequence of democratic impatience. Some politicians (George W Bush, Tony Blair) grew tired of waiting for the long-term advantages of democracy to reveal themselves and tried to speed up the process, with disastrous consequences. The wars fought after 2001 in Afghanistan and Iraq were designed to combat terrorism and to spread the merits of democracy. They succeeded in spreading terrorism and discrediting democracy. But the present plight of democracy is also a consequence of typical democratic complacency. By the 21st century, the pattern has become familiar enough to be taken for granted: nothing is ever as bad as it seems; democracy muddles through in the end. The financial crisis that began in 2007-08 was a result of that growing complacency. As the storm clouds gathered, politicians, central bankers and the general public all assumed that the situation would right itself. We carried on shopping and staring at our laptops. Stumbling around in the gloom, we nearly fell off a cliff.

How to steer a course between unwarranted complacency and unhelpful impatience is the democratic predicament. It is so difficult because countering complacency sounds impatient and countering impatience sounds complacent. This is the confidence trap, and there is no easy way out. Telling the Tea Party that the US can afford Obamacare is as futile as telling the architects of Obamacare that the Tea Party has a point. Telling Ukip that British democracy will eventually adapt to an influx of immigrants is as unhelpful as telling Guardian-reading liberals that Ukip are on to something. In a democracy you can always set short-term confusion against long-term strength, just as you can set long-term strength against short-term confusion.

Militiawomen training in Beijing. Photograph: Barcroft Media/Feature China

Militiawomen training in Beijing. Photograph: Barcroft Media/Feature China

Bouts of dictator envy are not going to go away. The site of the fundamental battles between autocracy and democracy may move to the east, as China and India eventually fight it out for the spoils of the 21st century. But the pattern is likely to repeat itself. Indian democracy is chaotic and cries out for decisiveness. Chinese autocracy is efficient but cries out for greater adaptability. In the long run, the more adaptable system is likely to prevail. But only if its short-term weaknesses don't get in the way. Meanwhile, western democracy faces its own version of the confidence trap. In Europe and America, the economic crisis has provoked a frantic outburst of muddling through as elected politicians try to keep the ship afloat long enough for the better days to return. Our politics is narrow and pragmatic, with our leaders attempting nothing more than to make sure nothing is broken beyond some future repair. But as they fight these familiar democratic battles, there is a danger that they are ignoring the bigger threat. Democracies have adapted to meet environmental challenges in the past. However, the risk of runaway climate change is different in scale and possible effects. It is something that no democracy can face with confidence. Yet, for now we do nothing about it. In the long-term contest between democratic impatience and democratic complacency, complacency may yet prove the winner. If it does, we will all lose.

Meanwhile, the muddle of democratic life creates the ongoing conditions for the spooks and the national security establishment to exploit our distraction to spy on us. As we continue shopping and staring at our laptops, they have the perfect opportunity to keep an eye on everything we do. The response to the recent exposure of their activities provides ample evidence of both democratic impatience and democratic complacency. Because we weren't paying attention to them, they were able to pay attention to us without our knowing it. Now that we know what they were up to, many democratic citizens feel anger and disgust. There is a lot of mud flying around: something must be done. But just as many express shoulder-shrugging indifference: why should we care about people listening in if we've got nothing to hide? Once Tesco and Google can collate information on the mundane details of our lives, it is hardly surprising that the secret services should choose to do the same. A similar mix of responses is on display from the politicians. Some are furious. Some are embarrassed by their ignorance. But plenty are relatively indifferent, on the grounds that it is what spies are paid to do. Secrecy, they claim, is the price of democratic security.

The pattern of democratic life is to drift into impending disaster and then to stumble out of it. Undemocratic practices creep up on us unawares, until the routine practices of democracy – a free press, a few unbiddable politicians – expose them. When that happens, democracies do not get a grip; they simply make the minimum of necessary adjustments until they drift into the next disaster. What is hard for any democracy is to exert the constant, vigilant pressure needed to rein in the forces that produce the crises. It is so much easier to wait for the crisis to reveal itself before trying to do something about it. The new information technology, far from solving this problem, has made it worse. We are more distracted than ever. The surfeit of information flowing around the world makes it practically impossible for anyone to keep secrets for long. But it also makes it practically impossible to secure broad democratic agreement for wide-ranging reform of public life. There is far too much noise, not enough signal. So we keep our fingers crossed in the hope we will muddle through.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου