Last week’s Danish election results, which saw the ruling Social Democrats ousted by a centre-right coalition that includes the far-right Danish People’s Party (PPP), reflect a growing domestic crisis of identity. While not unusual at the level of European national politics, the trend towards Euroskeptic populism is a signal of dissatisfaction with Denmark’s political governance.

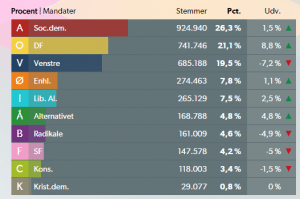

- Note: Soc.Dem. – Social Democrats, DF – Danish People’s Party, Venstre – the Liberal Party, Enhl. – the Red-Green Alliance, Lib. Al. – Liberal Alliance, Alternativet – the Alternative, Radikale – the Social Liberal Party, SF – the Socialist People’s Party, Kons. – the Conservative People’s Party, Krist. Dem. – the Christian Democrats. Source: http://www.dr.dk/nyheder/politik/valg2015/resultat

Last week, elections in Denmark saw the right-wing populist DPP soar to new heights, amassing 21.1% of the vote, as shown in the table.

Although slightly less than the 26.6% achieved in last year’s European Parliamentary election, this result still represents a very large share for a traditionally multi-party system, which tends to be dominated by parties of the centre-left and right.

What is the Danish People’s Party (DPP)’s agenda?

The DPP agenda is far from centrist. It is an odd mix of pro-welfare, socialist objectives combined with a deeply romanticised nationalism and fierce hostility to any force interfering with perceived “Danishness”.

Key issues include immigration, where the DPP favours a much tougher stance, despite an already strict policy in the area, growth in public expenditure, and renegotiation of Denmark’s participation in the European Union.

The party is also notorious for downright ridiculous propositions, such as levying a tax on English words in advertising, reintroducing physical barriers at the border and banning tertiary degrees taught in English. As of now, the DPP has never been in government, but whether it can avoid assuming responsibility this time, having surpassed the Liberals as the second-largest party, remains to be seen.

Developments in Denmark are in no way unique; there is a broader trend underlying the ascendance of fringe parties championing populist causes. Euroskeptic, nationalist parties of varying radicalism are gaining traction in Greece (Golden Dawn, Syriza), France (Front National), Spain (Podemos), Finland (True Finns), and Poland (Law and Justice Party).

Although less radical than DPP, Sweden has the Sweden Democrats, and Norway has the Progress Party.

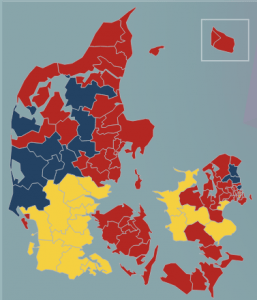

This trend exposes not just factions within Europe, the north-south “divide” and the mounting tension over the issue ofasylum seekers; it also reveals rifts domestically. A closer look at the geographical dispersion of votes in the Danish election reveals how the DPP’s support overwhelmingly derives from rural parts of the country, as exemplified on the map below (yellow areas indicate regions where DPP won a majority of the vote, red denote Social Democrat-majorities and blue represents Liberal domination).

The political priorities for the urban population differ substantially from those of the rural population. Since a municipal merger of 2007, and possibly even prior to it, it has been the perception of people in the countryside that decisions are made centrally, in Copenhagen, with little regard for troubles arising from emptying towns and decaying villages. A vote for DPP is, for some, an expression of discontent with the political governance, at the domestic and European level.

DPP addresses two issues, which make significant numbers of people uneasy; first globalisation, by proposing to close the borders and pull away from political participation in EU and international affairs – and second, urbanisation, by prioritising public services to a uniform standard and tearing down abandoned houses. This is not just a manifestation of political differences, it is also a showcase of a cultural clash, between traditional, nationalist family values and urban, well-educated, “managerial” politics.

“Globalization produces winners and losers, and large groups feel they’ve been left behind, no longer represented by mainstream parties. The parties of the left have become representatives of public-sector workers and the creative industries, while the right represents big business and finance, and both are rather liberal in social values. That leaves large segments of the population feeling angry and unrepresented, and new parties are emerging with a different language.”– Mark Leonard, director of the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Liberals and DPP – an odd couple?

At the time of writing, Lars Løkke Rasmussen has announced that he is aiming for the formation of a minority government, indicating that the political differences between the right-wing, “blue bloc” parties were too great. According to DPP’s Peter Skaarup, the most likely outcome is a minority government consisting only of the Liberal Party. The DPP will nevertheless wield significant influence, backed by their 37 mandates (against the governing Liberals’ 34).

DPP has announced four “indispensable” demands as conditions for joining a coalition with ruling Liberals: stricter policy on EU matters, reintroduction of border controls, a firmer immigration policy and growth in public expenditure of 0.8%.

Of those, tighter rules on immigration might be realized, seeing as the Liberal Party has campaigned to roll back immigration law to the 2011 standard, which was tougher than it is today. Expenditure growth, however, goes straight against Liberal objectives, but could possibly be accommodated, given the uncontroversial nature of raising public spending in Denmark.

Border controls involving barriers and complete checking of all entrants is at odds with the Schengen agreement, although a feasible compromise would be intensified random searches, and granting the tax authorities and the police more powers in checking identity, nationality and rights of residence in an area up to 20 km from the border.

This right was established at the European Court of Justice in 2012, where Dutch border control practices were defended. Finally, the DPP and the Liberals agree on a more Euroskeptic stance, and will in all probability support Britain’s demand for renegotiation of EU membership.

sourche: http://globalriskinsights.com/2015/06/danish-election-results-reflect-a-domestic-identity-crisis/

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου